Sunbursts, starbursts, or the star effect – however you decide call it – is a neat way to add a little flare to your photos (pun intended). Luckily, creating a sunburst in your photos is pretty easy and something you can try today. In this article I describe how to create an awesome sunburst in a few simple steps.

Use a Single Source of Light

First and foremost, you can only get the star effect from a distant, single point of light, such as the sun, a street lamp, Christmas lights, city lights, and certain kinds of reflected light. It is impossible to create a starburst if the source of light is diffuse in any way. For example, you will be able to get the sunburst effect of the setting sun on a perfectly clear day, but if there is a lot of humidity or some low stratus clouds, then it will be more challenging to get a good star effect.

Understand Diffraction

The whole reason we able to turn a single source of light as powerful as the sun into a star-like shape is because of diffraction. Light waves travel in a straight line until they pass through an opening like a pinhole, and then the light waves bend and spread out on the other side. The extent of light bending depends on the wavelength of light and the size of the opening the light is passing through. This is called diffraction. In a camera lens, the aperture opening controls how light is diffracted before it hits the camera sensor.

In photography, we typically want to avoid situations that increase diffraction because this can lead to soft images. However, in order to get sunbursts or the star effect, we actually want to increase the diffraction (or bending) of light. We can achieve this in two simple steps: adjusting the aperture and slighting impeding the light source with another object. Both of these are described in more detail below.

Use a Narrow Aperture

The first step to achieving a sunburst is to use a narrow aperture, or a high aperture number. The actual f-stop you use will depend on your lens, the brightness of the light source, and the exposure requirements for the scene. I have found that I get the best sunbursts at about f/16-f/25, although I have been able to get them as low as f/11 and as high as f/32. Again, it really depends on the lens you use and how bright the light source is. Some photographers will recommend never shooting fully stopped-down (at the highest number aperture) because by increasing diffraction you run the risk of softening images. I haven’t personally found this to be a major issue, but it is something to keep in mind as you are experimenting.

Partially Block the Light Source

Another way to increase the star effect is to partially block the light source. This is actually works best when the source of light is super bright, like the sun. It likely won’t make a difference with weaker light sources, such as a street lamp. Partially blocking the sun with objects, such as a mountain peak or branches or a hand with the “ok” sign, will make the sunburst much more pronounced. The effect is increased because by slightly impeding the passage of light, the diffraction of the light is increased before it hits your aperture.

A silly trick that I use is to squint my eyes as I look at a scene and scope out whether it would work for a sunburst photo or not. If I can see the pointed rays forming while squinting, then I likely will be able to get the sunburst in camera. Sometimes, you need to move around a bit to get the sun passing through just the right spot to get the effect you want. A few inches can make a huge difference, so it is good to experiment. Oh, and I’m sure it goes without saying, but be sure to properly protect your eyes while squinting at the sun and do this at your own risk.

Choose the Right Lens

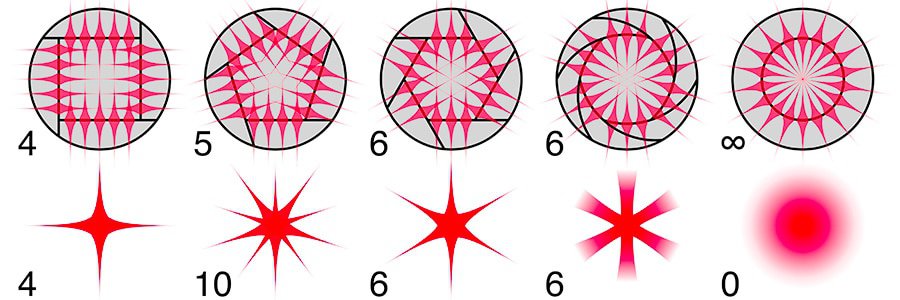

How many diaphragm blades does your lens have and what shape do they form? This will determine what your sunburst will look like. The aperture of a lens is formed by several flat blades that basically form an iris or diaphragm opening. The light coming into your lens will be diffracted by the edges of the blades, and so the number and shape of the blades will dictate the number of rays and pointedness of your sunburst. An even number of blades will give you an equal number of pointed rays, whereas an odd number of blades will give you twice that number of pointed rays. For example, if your lens has six blades you will get six rays, but if your lens has nine blades, you will have 18 rays.

If the blades in your lens are straight, then shape of the diaphragm opening will be polygonal, and you will get more of a pointed effect. On the other hand, if your aperture blades are rounded (less polygonal), then the pointed ray effect may be lost a bit.

Use a Tripod and Remote Shutter Release

Using a tripod is less important if you are photographing in the middle of the day, but it is definitely a necessity if you are going to do any cityscape or night-time photography. The longer shutter speeds required in low light situations make it impossible to handhold those types of shots, especially if you are trying to get the star effect of lights and have the aperture stopped way down. If you are looking to invest in a tripod, check out the recommended tripod list on Improve Photography. It’s also good practice to have a remote shutter release as well, although it isn’t required. The purpose of the remote release is to be sure to avoid any camera shake that can occur while depressing the shutter button, but a work around is to just use the timer function and have a little patience.

Expose for Highlights

Since to create the star effect you have to photograph a direct light source of some kind, it is best to expose for the highlights. In this situation, bringing up the digital information in the shadows is a little more forgiving than trying to recover the highlights when exposing for the shadows. In fact, if you do expose for the shadows, the light source will be so blown out that it would be impossible to recover those highlights in post-processing. That said, it is not uncommon to have the center of the light source blown out somewhat. The challenge is to find the correct exposure where you can bring down the highlights and bring up the shadows enough to get the detail in the sunburst you want and the other elements in the image. Another way around this challenge is to try high dynamic range (HDR) photography, where you take a few different exposures and then blend them in post-processing.

Experiment

Now that you know how to create sunbursts, starbursts or the star effect, it’s time to experiment with it and have some fun. It’s a technique that can add mood or intrigue to a photo. It’s not for everyone or for every situation, but I enjoy playing around with it nonetheless. Find ways to be creative, such as using reflected light like in the image below or experimenting with how to get multiple bursts from a single light source.

When I read the title I thought, “What? F/22 – End of article.” I was pleasantly surprised to see the detail, thought, and great explanation that went into this. Photography lesson learned… (again), About the time you think you know it all… Well done Brenda!

Thanks so much, Rick! 🙂

Can you actually see it (the starburst) through the view finder or do you have to check it after the photo has been shot? This might seem like a stupid question, but I am learning.

You can see it in live view before you snap the photo. I’ve used that in some of the starbursts I’ve taken, in particular when the sun is coming through tree branches, and the branches are moving from the wind causing the starbursts to appear/disappear. 🙂

Thanks, Nathan!

No problem…great article!

Not a stupid question at all! I haven’t been able to see it through the viewfinder, but as Nathan said, you can see it in Live View (most of the time). I don’t have a mirrorless camera so I’m not sure whether you can see it through the EVF on mirrorless. I assume it does. Does anyone out there know?

Hmm…never tried it on a mirrorless but I’d assume the answer is yes, since the EVF is just a screen like a mini live view. I have a mirrorless as well so can give it a try and report back.

Interesting…I correct myself to say “it depends”. What I found on my OM-D E-M10 is I didn’t see the bursts in my EVF but the reason behind it is that the aperture does not close until the shutter is depressed. I would assume it would be visible in an EVF, provided that the aperture physically changes while adjusting your exposure settings, as opposed to exposure adjustments and light meter readings being “computerized”, as what seems to happening in my Olympus.

Hmm – that’s interesting! Good point about whether or not the aperture is actually at the f-stop selected or if it doesn’t close until the shutter is depressed. I wonder if that is camera dependent. I don’t know much about mirrorless camera technology! Thank you for checking it out and reporting back.

I don’t know much about it either. I assume it’s camera-dependent but it could be the behaviour of all mirrorless cameras.

How do you know the # and shape of the blade?

Great question. I wonder the same….

Hi Lois and Veronica – the best way to determine the shape and number of diaphragm blades is to check the specs on the lens from the manufacturer.

Luminar 2018 has a filter that can be added in PP to create the “sunburst” effect. While I have Luminar installed, I have no affiliation with the company and simply offer a couple of links that show something about the effect.

https://www.blipfoto.com/entry/2378982723613100019

http://shuttermuse.com/how-to-add-sun-rays-to-a-photo-with-luminar/

The filter can be infinitely adjusted as to position, number of bursts etc to the point that it can be placed off the document to have a burst peak through clouds etc at the edge of an image.

There are some videos available showing how to work with the effect as it is a new filter among 50 that are in the Luminar 2018 package.

Thanks for the info, Murray!